In 2018, Uganda started taxing social media use. Responding to criticism of the tax, President Yowerik Museveni wrote, “Governments normally tax consumer items with inelastic demand… whose demand does not decline even when the price goes up… Alcohol, tobacco, etc. fall in this category because of addiction; social media use is definitely a luxury item.”

Museveni not only compared social media to a harmful addiction, but also suggested that it’s a luxury because it is used for “chatting, recreation, malice, subversion, [and] inciting murder.” Such strong language as well as past instances of Museveni crushing opposition indicated to several media sources that the Social Media Tax (SMT) was likely a way to subdue Ugandan opposition.

So is social media really a luxury in Uganda? Or is it a political resource for the opposition? I studied survey data from Ugandan social media users to find out.

Uganda’s Social Media Tax

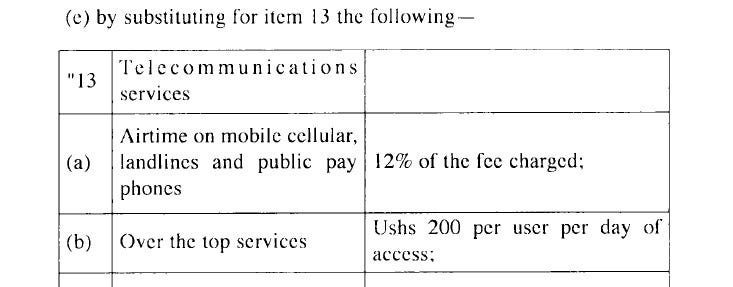

The SMT in Uganda was legalized through a 2018 amendment to Section 13 of the 2014 Excise Duty Bill. The amendment levies taxes on over-the-top (OTT) services, which are media provided directly over the Internet, and requires each user to pay 200 Uganda shillings per day for access. The government has listed several big-name social media sites like Facebook and Twitter as OTT services that require Ugandans to pay this tax.

Figure 1. Section 13(b) in the 2018 Excise Duty Amendment Bill adds taxes for over-the-top services including social media.

Museveni claims that the tax will improve the economy by preventing foreign social media companies from benefitting off Uganda. However, such anti-foreigner rhetoric is often used to justify solidifying power, raising red flags about his true motives behind the SMT. Many believe that since the government decides which social media sites are considered OTT services, it aims to use the SMT as a means of censoring the opposition instead of limiting luxuries.

Social Media as a Luxury

Although social media is mostly used by more economically prosperous Ugandans, it does not have inelastic demand, and is therefore not the type of luxury Museveni describes. As of 2017, 17% of Ugandans used social media at least once per month as a source of news while 7% used it on a daily basis. Ugandans who use social media tend to be more economically prosperous than those who don’t. As depicted in the graphic, social media users speak more English, are better educated, work in more full-time positions, and have better living conditions.

Figure 2. Demographics of Social Media Users in Uganda.

This economic prosperity of social media users makes sense — presumably, richer people are the ones who can afford devices that connect to the internet, internet connection itself, and leisure time to use social media. However, unlike the luxury Museveni describes, social media does not actually have inelastic demand.

“Inelastic demand” is where consumers will continue to buy something even if the price is raised. In the months following the SMT, this has proven untrue about social media. While the tax has only been in effect for one year, there have been several nearly immediate results including more than 2.5 million people stopping their subscriptions to OTT services and 1.2 million people quitting paying for the SMT.

What this suggests is that calling social media a luxury with inelastic demand is not entirely accurate because although social media users tend to be more prosperous, they still aren’t willing to continue using social media as the price increases.

Social Media as a Political Resource

While Museveni’s claim that social media is a luxury isn’t correct, what holds true is that Ugandans using social media are much more likely to not support Museveni.

32% of Ugandan social media users would vote for the Forum for Democratic Change, the leading opposition party, as opposed to only 14% of non-social media users. 36% of users believe that the 2016 elections were not free and fair, as opposed to only 17% of non-users. Only 15% of users wanted the age cap on running for the presidency (which Museveni is about to exceed) removed, as opposed to 26% of non-users.

As these examples show, social media users often align with several anti-government stances. In fact, their trust in the government is low across all governmental organizations, including the Presidency and the Electoral Commission, as shown in the following figure. Notably, social media users only have more trust than non-users in one field: opposition political parties.

Figure 3. Trust in Government Organizations. The listed percentages are the differences between the percent of users and non-users who trust each organization.

*NRM = National Resistance Movement, Museveni’s party

These findings are particularly interesting because 4% of social media users work for the government as opposed to only 1% of non-users. And, even among only government employees, across most (five out of eight) of these categories, social media users have less trust in the government.

Therefore, by limiting social media access, Museveni is able to prevent people who support the opposition from accessing a primary source for their news. Regardless of Museveni’s statements to the contrary, social media is very much not a luxury. However, it is something that people who support the opposition use and the SMT does seem to be an effective way of limiting resistance.

Uganda must get rid of the SMT or perhaps remove social media from the list of OTT sites. In his justification for the SMT, Museveni shouldn’t be describing social media in Uganda as a luxury for the rich, but rather as a resource for everyone, including his opposition.

The statistics and graphics in this article are based on primary research I conducted using Afrobarometer Round 7 data from Uganda.